|

published in: "The Journal

of the Orders and Medals Society of America", volume 51,

number 4, pages 30-32, and received the

OMSA

Literary Medal 2001.

The

collecting and study of orders, decorations, and medals

is an interdisciplinary enterprise that requires some

knowledge of history, art and numismatics pertaining to

fakes is especially important. Some fakes are easy to

spot, but others are so deceptive only an expert on the

award in question can see through the fraud. Among the

most deceptive fakes are those produced by the

electroplating process; however, these fakes can often

be detected by collectors who have no particular award

expertise but do know how they were made.

Illustrated are the first

and second issues of the Nassau Life-Saving Medal. The

first issue was awarded on 13 February 1843 by Nassau’s

Duke Adolph. This silver medal, which is 30mm in

diameter, was designed by Christian Zollmann. Is It was

not meant to be worn. On the obverse is a large profile

head of a young Duke Adolph facing the right, and

encircling the profile is the inscription ADOLPH

HERZOG ZU NASSAU in raised letters. The reverse is

plain except for the inscription FUR/RETTUNG/AUS/LEBENSGEFHR

(literally, “For Rescue Out of Life-Threatening

Danger”) in the bottom. A total of 54 first-issue medals

were struck and awarded.

In 1865, 30 silver

life-saving medals of a new design and also 30mm in

diameter we struck. The 1843 reverse was retained, but

the obverse now featured the profile of an older looking

Duke Adolph facing to the left, and the name of the die

sinker, “KORN,” was added at the base of the

profile in small raided letters. Moreover, the new

design incorporated a suspension device and solid red

ribbon so that the medal could be worn. Only 5 of the

second issue were awarded, and the remaining 25 medals

were melted down in late 1866.

Thus both issues, and in

particular the second issue, are extremely rare and

highly prized by collectors of the awards of the German

states. Small wonder then that someone took the effort

to make the illustrated second issue, which is a fake

produced by electroplating.

Before closely examining

this fake, it is first necessary to briefly describe the

electroplating process. The principle was discovered by

Faraday in 1833, and the process was patented in England

in 1840. The purpose of electroplating is to transfer

and bind the atoms of one metal to the surface of

another metal or to the surface of an object coated with

a conductive material. Electroplating requires a DC

power supply, often a battery, a chemical bath called

the “electrolyte,” and an “anode” or positive pole at

one end of the bath and a “cathode” or negative pole at

the opposite end. When the anode is connected to the

positive pole of the power supply and the cathode to the

negative pole of the supply, electrons stream from the

metal of the anode to the cathode. This stream is part

of the electrical current that flows from the positive

pole of the power supply to the anode, through the

electrolyte to the cathode, and then from the cathode to

the negative pole of the power supply, thus completing

the circuit. Electricity is merely a stream of electrons

through a conductor, which can be either a metal wire or

the chemicals in a plating bath.

The shedding of electrons

from the anode simultaneously produces positively

charged atoms or “ions” of the metal of the anode. The

ions are attracted or pulled to an excess of electrons

gathering at the cathode. These ions bind with free

elections at the cathode producing neutral atoms of the

metal that attach to the cathode to form the plate. It

is important to note that the source of the plating

metal need not be the anode. Electroplating is often

accomplished by using a no reactive anode, such as

platinum, and an electrolyte containing a salt of the

plating metal. The chemistry is the same except that the

source of the plating metal is the electrolyte instead

of the anode. Of course, the chemical reaction is the

electroplating process is more complicated that

suggested by my simple explanation, and a number of

important technical aspects must be considered, such as

the duration of the process and the composition of the

electrolyte, to achieve the desired consistency and

thickness of the plate.

|

|

The

first step in producing a fake medal by

electroplating is to make an obverse and reverse

mold of the original. Early molds were made using a

mixture of bee’s wax and graphite, but today nearly

prefect molds can be achieved with the silicone

rubber compounds that are sued to make dental

impressions. After the mold is make, the inside is

covered with a conductible material, such as

graphite, and then the mold is attached to the

cathode in an electrolyte bath that has a copper

anode. When current is applied, a thin copper plate

or shell forms on the inside of the mold. Once the

obverse and reverse shells are make, the inside of

the shells are filled with a soft metal and the two

halves are soldered together. Copper is initially

used because it is less expensive than sliver, is

easy to plate, and has an extremely durable surface.

Later silver is electroplated to the assembled

copper shells. Silver plating usually involves the

use of a no reactive anode and an electrolyte

containing silver dissolved in nitric acid or a

cyanide solution. |

Electroplated fakes are

typically very difficult but not impossible to detect.

The detail can be perfect, and the surfaces are as

smooth as the original, unlike cast fakes which

typically have porous surfaces. In addition, a filler

can be used inside the shell that gives the fake the

same weight as the original. Nonetheless, the process

itself provides knowledgeable collectors with certain

indicators that can be used to determine whether or not

a particular medal has been produced by electroplating.

Consistent application of the following four indicators

should greatly aid collectors in avoiding the misery

brought by the purchase of one of these clever fakes:

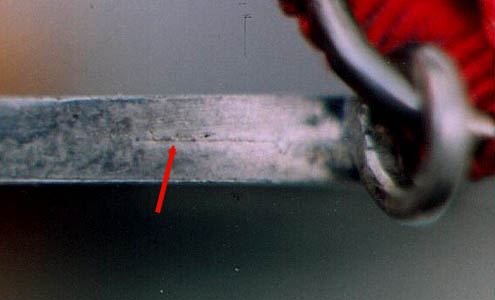

First and foremost, it

must be remembered that the fake was not make as one

piece but consists instead of two halves that were

soldered together. This means that despite the best

efforts of the counterfeiter to polish out he solder

seam, a portion of the tell-tale seam almost always

appears on the edge of the medal. That portion of the

seam visible on the edge of the fake second-issue Nassau

Life-Saving Medal is shown in the enlargement below.

Secondly, the fake

“sounds” different. Lead is often used to fill the

inside of the fake, and sometimes antimony is added to

the lead to give the fake the same weight as the

original. However, when tapped by a hard object, the

fake with its lead filler sounds, “dead” compared to a

solid silver piece, which has a clear metallic sound.

Thirdly, collectors

should carefully examine the medal for areas where the

silver plate has worn off and the copper plate

underneath shows through. Simply put, medals struck in

solid silver can’t have signs of copper.

Finally, one must also

carefully look at the medal’s detail. A fake produced by

electroplating can have flawless detail, but this in not

always the case because the surface of the fake is only

as good as the surface of the mold. Very often, there

are tiny deficiencies in the mold that appear in the

final product. In the next enlargement, several problems

are evident in the letters of the die sinker’s name on

the obverse of the fake second-issue Nassau Life-Saving

Medal.

Fakes produced by

electroplating are much harder to detect than cast

fakes, and counterfeiters have been greatly aided by a

lack of knowledge by both dealers and collectors of the

electroplating process and its indicators. To make

matters worse, electroplated fakes are appearing in the

market in increasing numbers. I remember from my days as

a young collector in Germany that German World War I

aviation badges were almost impossible to find. The

originals are still hard to find in Germany, but what is

new is that since the late 1980’s electroplated fakes

can be seen wherever awards are sold. The tide can only

be stemmed though education, and that is the intention

on this article.

© A. Schulze Ising,

VII/00

|